ELABORATING ON THE DANGERS OF ELECTRIC VEHICLES

BY ALLISON ROGERS

Does the idea of working with electric vehicles give you the EV-jeebies? You’re not alone—many in the industry aren’t so keen to work on what the industry markets as the vehicles of tomorrow.

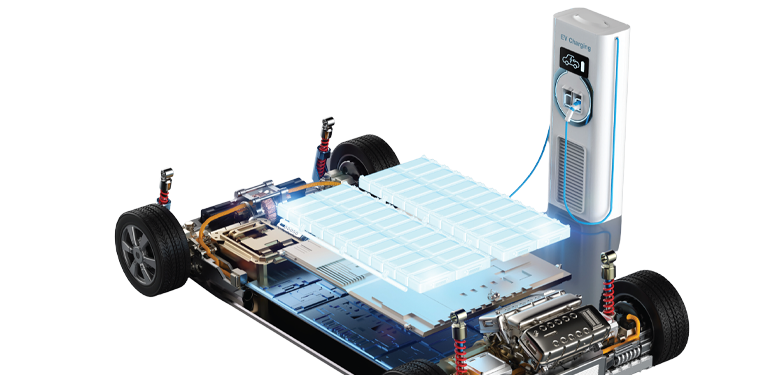

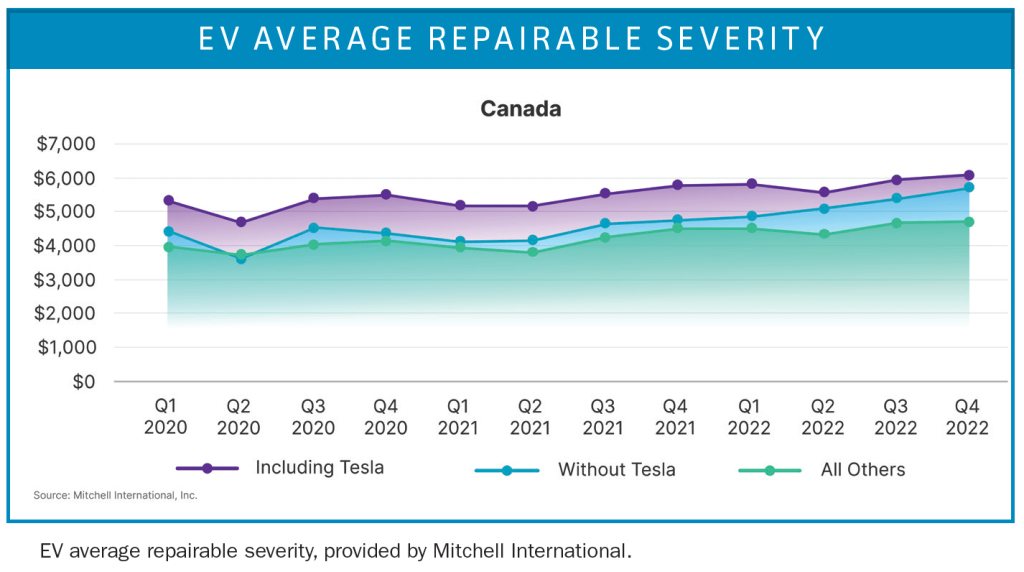

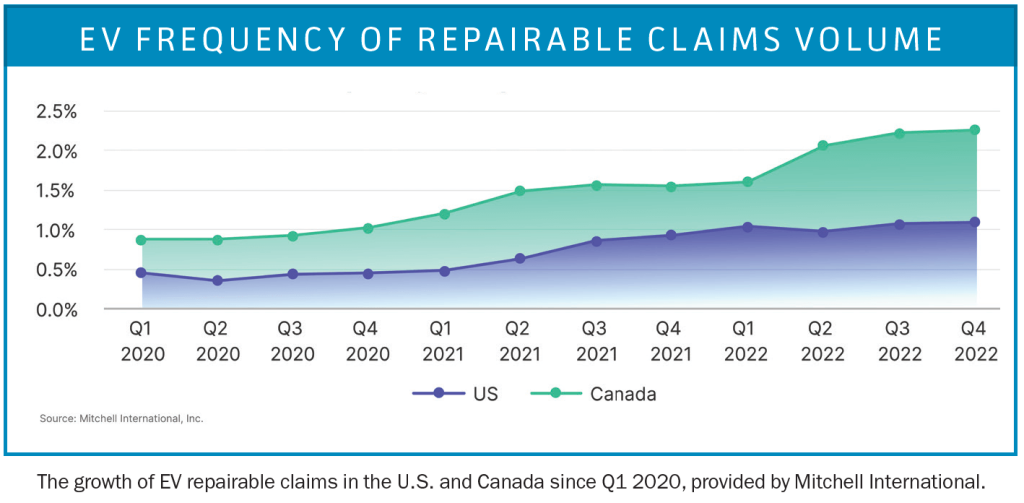

Regardless of any qualms you may have, a reckoning is upon us. According to data from Mitchell International, more than two percent of repairable claims processed in Canada in 2022 were electric vehicles. Moreover, those EV jobs added, on average, two days of cycle time and six additional labour hours, said Ryan Mandell from Mitchell. The Canadian government wants 100 percent of new vehicles sold to be electric by 2035…just over ten years from now.

In other words, we need to get to learning. We investigated some of the most common concerns around EV repair—the risk of fire, hazardous chemicals, worries of explosions and handling high-voltage units—and collected our findings below.

IS IT HOT IN HERE OR IS IT JUST EV?

According to research from the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA), lithium-ion batteries will typically burn when one of four situations occur: improper charging, excess draw on the battery, swelling and/or rupture of the battery due to poor design or physical damage—potentially caused by a collision—that causes internal parts of the battery to make contact in an unmanaged way.

In a bodyshop setting, the first signs of an EV fire may be a sweet, cherry-flavoured bubble-gum smell, as described by Tesla. You may also use thermal imagery capabilities to scan battery systems, which should have a uniform heat signature. Some more obvious signs are smoke, heat and, obviously, fire. An electric vehicle fire burns much hotter than a regular vehicle fire—so it’ll take a lot more water to extinguish electrical flames. Batteries are often housed deep within the vehicle and are a self-sufficient source of oxygen. And, as they burn, EV batteries release super-heated gases and toxic vapours, from carbon monoxide and soot to particulates containing oxides of nickel, aluminum, cobalt and hydrogen fluoride.

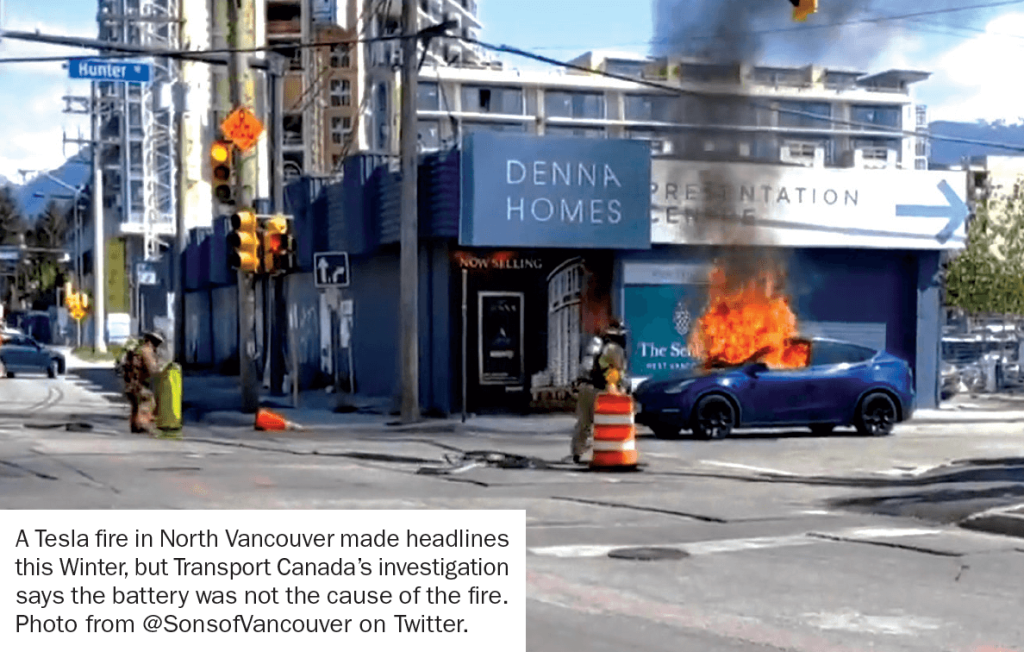

Thankfully, the experts assert that electric vehicle fires aren’t as common as the mainstream media may portray them to be. “For every 100,000 gas-powered vehicles, there are about 1,600 vehicle fires. With 100,000 electric vehicles, there are about 25 vehicle fires,” David Giles, co-founder of All EV Canada told Bodyworx in 2022. “The risk is very, very low—far lower than in a gas-powered vehicle.”

On the off chance an EV catches fire at your workplace, many OEMs advise first responders to let the vehicle burn in a controlled manner and shift their focus to protecting the surrounding area.

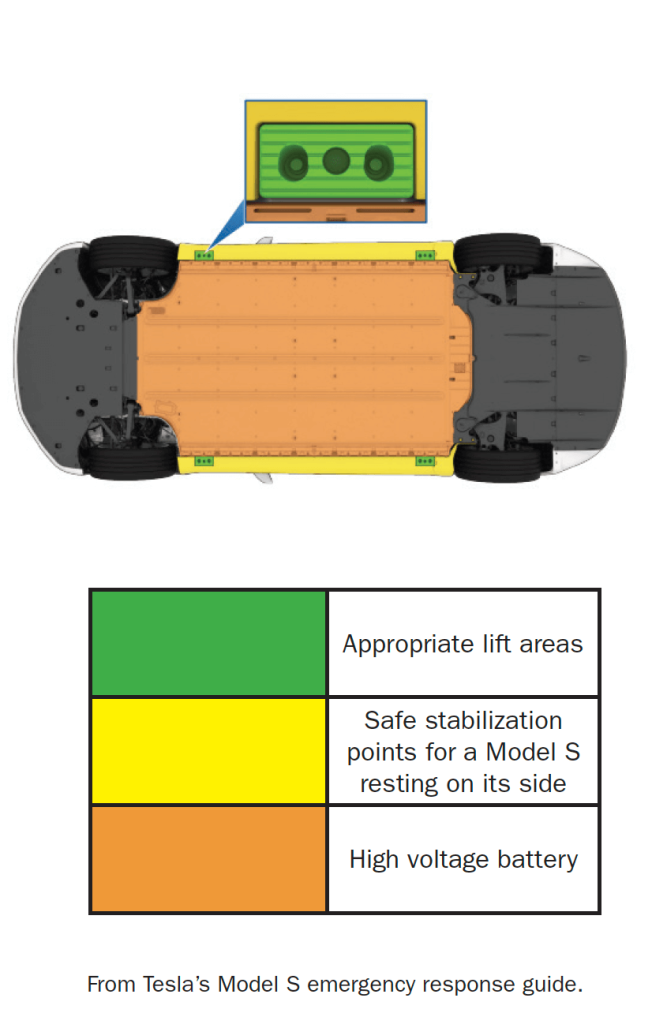

Other methods with more limited testing include large thermal battery blankets to smother the vehicle and deprive the fire of oxygen or the use of slide-in containers that seal shut and douse flames from the inside out. In its Model S emergency guide, Tesla stresses that a burning vehicle should not be lifted or manipulated unless first responders are trained, equipped and familiar with the vehicle’s lifting points—designated lift areas where it is safe to stabilize the battery. Making contact with any other part of the vehicle in a fire scenario presents a great risk. As a technician, painter, front-end staff or anybody that’s a day-to-day regular in the bodyshop, it’s unlikely that putting out EV fires is in your job description. The most important thing for you to do in this situation would be to get yourself and others to safety as fast as possible.

LOOKING FOR LEAKS

EV battery explosions are even rarer than EV fires, but not entirely unheard of. In the event of a collision, components and battery cells may be damaged—i.e., there could be leaks in battery fluid or other highly toxic and flammable materials. One spark, plus a leak, and you’re on the brink of a major disaster. When a vehicle is brought in, staff need to have the necessary knowledge and skills to manage the risk associated with repairs in the event of considerable damage.

ASSESSING SHOCK VALUE

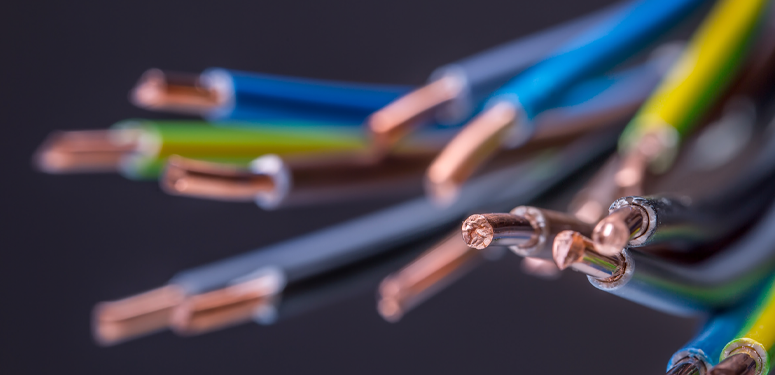

The Corporation des Concessionnaires Automobiles du Quebec (CCAQ) says electric shocks can cause tickling sensations, burns and, in extreme cases, death. That’s why it’s critical that autobody repairers understand and are familiar with wiring colour codes, and never assume that a battery has already been de-energized.

Insulated electrical gloves (1000V) and safety boots equipped with shock-resistant protective soles—indicated by the ohm symbol (Ω). Note that the resistance to electric shock decreases rapidly in the presence of moisture and with wear and tear, says the CCAQ. When a battery is compromised, high-voltage wiring harnesses are unpredictable, leading to increased risks of shock hazards. Further, when damaged lithium-ion and nickel-metal hydride batteries are vulnerable to stranded energy—meaning the unit is not able to spend its stored and potentially dangerous energy after a collision.

Hopefully, your takeaways from this article do not persuade you to run for the hills in search of another industry. In truth, it’s just a learning curve—but change is hard, even if you’re one of those people who say they like change.

And just remember, even legacy automakers like Ford say that “most electrical accidents are the result of incorrect or careless action, not faulty equipment.” So, stick to the books, and you’ll be set for a future in repairing EVs.