BIG STRIDES FOR AUTOMOTIVE PAINTERS

BY ROS MACDONALD

When asked how collision repair has changed over the last two decades, most members of the industry will simply respond with, “how hasn’t it changed?” Automotive coatings are just one of the industry verticals to have been uprooted in recent decades. If we flip back the calendar thirty years or so, manufacturers were just beginning to use base coats and clear coats, which provided new and vibrant colours for painters and consumers alike to enjoy.

Collision repair centres followed suit by implementing the two-stage process— a method initially reserved for high-end repairs. Prior, the norm was to use single stage materials, including acrylic enamels that would leave young painters today scratching their heads in confusion.

“Now, we use tri-coats that give brilliance and depth to the colour,” explains Danny Marques, chairperson for the Automotive Collision Repair Department at Okanagan College.

There has also been significant progress in the technology used to match paints. Today’s scanners—spectrophotometers—take an image of the car’s paint colour and create a paint formula based on the scan—a far cry from manually matching with a spray card and squinted eye. “A painter still needs to assess whether or not that will be accessible to use, but the support from the technology is much better,” said Marques.

In 2007, the government created legislation around the use of pollutants in auto painting, prompting the collision repair industry to switch to water-borne paints. Fortunately, the water-borne paints also reduce clean-up time, cost of disposal, and solvent waste. “Changing to waterborne paints was a challenge at first, but once we made that transition, we never looked back,” said Vince Gareau, owner of CSN L-Jay Autobody in Alberta.

Today, automotive painters are far more aware of health risks associated with their professions—and act accordingly. “I still remember the days where painters were wearing dust masks with cigarettes poking through the masks while they painted,” explains Scott Kucharyshen, head of Saskatchewan Polytechnic’s Autobody Program.

Without the proper personal protecting equipment, hazardous chemicals in automo tive coatings can lead to long-term lung and neurological issues, and other problems like asthma and hives.

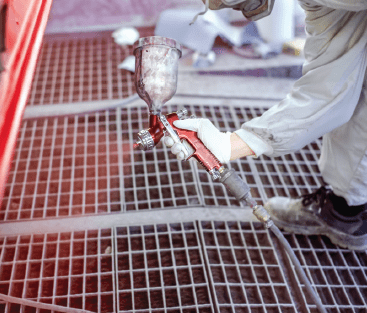

“Now, everyone is wearing paint suits, fresh air respirators, latex gloves. Today’s nitro gloves are also far better; the ones we use won’t dissolve in gun wash,” said Barry Lee, instructor at Red River College Polytechnic.

The technology used to spray the paint has also improved immensely, making leaps and bounds in terms of efficiency. Thirty years ago, automotive painters were wielding low-volume-high-pressure guns—with subpar transfer efficiencies, by today’s standards. High-volume-low-pressure guns were just around the corner, followed by the newer reduced pressure guns.

“Modern automotive spray guns, the HVLP and RP guns, must have minimum 65 percent transfer efficiency,” said Kucharyshen. These improvements benefitted the environment, the worker, and the bottom-line. Another key step in meshing with modern automotive painting was getting down with the downdraft.

The dated cross-draft booth model would get feed air from right inside the shop—where body-working colleagues stood kicking up tornadoes of dust. Cross-drafts were also susceptible to furnaces, which had to be set warm enough for the air to work in the first place.

“In one shop that I worked at, we couldn’t work when it got to be -30°C because we couldn’t keep the air warm enough to go through the booth,” recalled Kucharyshen. “The new downdraft booths, on the other hand, include their own independent furnaces, and have a lot more air movement, giving painters more flexibility.” Of course, few advancements come without a price tag. Waterborne paints, for one, are not cheap.

“[These costs] can be absolutely be justified in businesses putting out a lot of work,” said Lee. “Once [the industry] finds a way to make it cheaper, we will see these advancements adopted across the board.”

If the past thirty years have made anything clear, automotive painters are undoubtedly ready for the challenge.